Suzuki’s production turbo bike is nearly here

By Ben Purvis

Motorcycle Journalist

23.10.2017

Suzuki has long been at the forefront of the development of turbocharged motorcycles. Its Recursion concept bike wowed us four years ago and now it looks like the company is on the verge of revealing its production-ready offspring.

A newly-filed patent application from Japan is the latest in a series of that have revealed how the project has been developing over the years since its initial showing in concept form. Over that time the parallel twin layout has remained, but much else has changed.

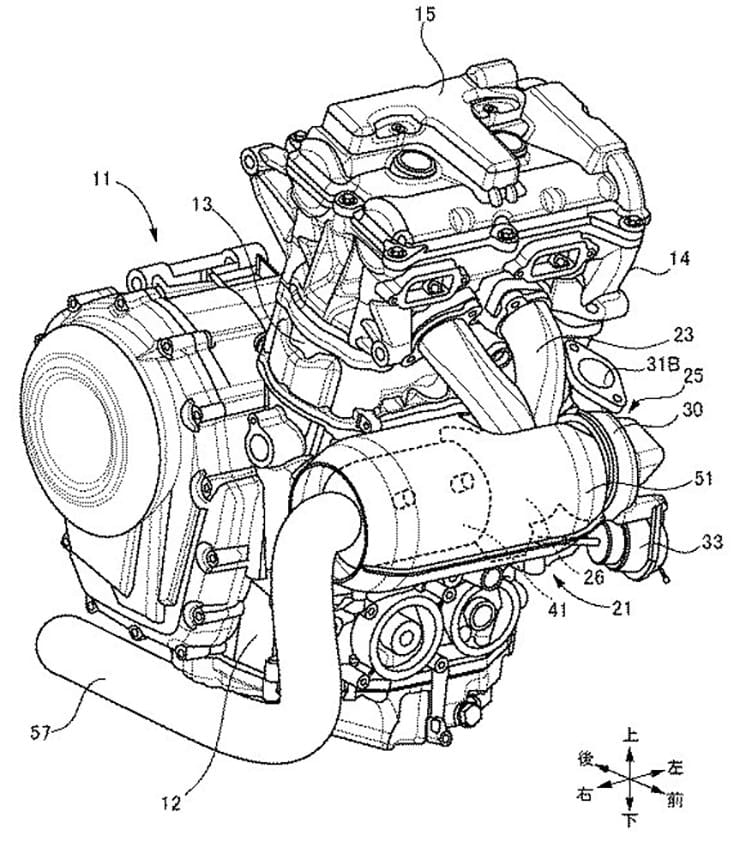

Most notably, the engine has developed from a single-overhead-cam, 588cc twin developing 100hp, as shown in the Recursion, into a DOHC twin of unspecified size. That motor was dubbed XE7 – perhaps a hint at a 700cc capacity – and shown two years ago. It was notable not only for being turbocharged but for the sensible, production-ready elements of its design.

Now the latest patent gives a further hint as to how that engine will be mounted in a bike. And given that the original Recursion broke cover at the Tokyo Motor Show in October 2013 and the engine came out at the same event in 2015, there are high expectations for some big turbo-related news from Suzuki at the next running of the show. It opens on 25 October.

The switch from the Recursion’s aluminium beam frame to a steel trellis design was revealed some months ago in another patent. This new one, which emerged in Japan last week, appears to confirm that. There’s still no indication of the bike’s styling, though.

Other changes include a mode from an under-seat intercooler, as used on the Recursion, to one that’s in a unit with the airbox mounted above the motor.

What the latest patent shows most clearly, and what it revolves around is a mundane but necessary element that can only be a clear pointer towards a mass-made, road-going bike; the catalytic converter.

Emissions rules have been playing an ever-larger part in new bike development, particularly the Euro4 regulations now in force in Europe. In Japan, similar new emissions limits came into force in September 2017. So any manufacturer working on a new bike needs to think carefully about emissions from the start.

Turbo engines are already at an advantage here. They can make lots of power and torque from a relatively small capacity, without having to resort to stratospheric revs. Emissions and economy are some of the driving forces behind the development of turbocharged bikes. But mounting a catalytic converter in the exhaust is complicated by the addition of an exhaust-driven turbo.

Doubly complex is the fact that the latest emissions rules impose short warm-up times on engines. Catalytic converters don’t work properly until they’re hot, and with less time to reach operating temperature, the pressure is on to move them nearer the engine’s exhaust exit, rather than positioning them back inside the silencer casing.

On a turbo bike there’s also pressure to put the turbocharger as close to the exhaust ports as possible; shorter pipes reduce turbo lag, which is far more noticeable on a bike than in a car. With the throttle operated by hand rather than foot, and much lighter flywheels allowing bike engines to react more quickly than cars, any delay in response is much more apparent to a rider than to a driver.

The result is that on the upcoming Suzuki turbo bike, the turbocharger and catalytic converter are vying for the same position on the exhaust pipe.

Suzuki’s solution? Combine the two.

This picture shows the combined turbocharger and catalytic converter that’s destined to appear on Suzuki’s production turbo bike. You can see how the exhaust manifold merges the gasses from the two cylinders as soon as possible and funnels them straight into the turbine. This in turn spins the compressor, on the far side of this image (marked ‘30’), which sucks in fresh air, compresses it and forces it out of the pipe marked ‘31B’ which will be connected to the pressurised airbox. You can see higher on this page an image of the XE7 prototype engine, which shows how the pipework and turbo are arranged.

Having done this work, the exhaust gas goes straight out of the turbo into the catalytic converter, marked ‘43’. That was missing on the XE7 engine, but is clearly needed for the production bike. By putting the catalytic converter here, it’s guaranteed to get to the extreme temperature needed to make it operate. Cats tend to work at about 750°C, while the hottest parts of the turbo could be in excess of 1000°C.

Unsurprisingly, much of Suzuki’s new patent is devoted to the design of the heat shield mounted over the turbo and catalytic converter! (Marked ‘51’ on the drawings)

The upcoming production turbo twin isn’t the only boosted Suzuki project on the go at the moment. Just weeks ago we revealed that the firm has plans for a turbocharged V-twin cruiser and now another patent application reveals an idea for another parallel twin design.

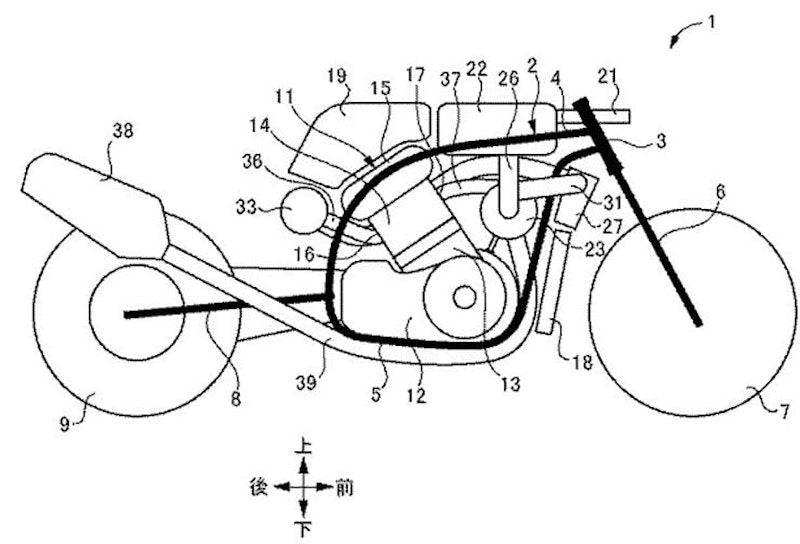

It’s clearly very much at the conceptual stage, quite unlike the almost production-ready design in the previous patent. But this idea shows how the addition of a turbocharger could lead to a rethink of some of the basics of how we expect a bike to be laid out.

The patent shows the engine’s cylinders tilted backwards in the chassis, rather like BMW’s G310, Yamaha’s YZ450F or Honda’s Moto3 bikes. But unlike those designs, which also use a reversed cylinder head, with the intake at the front and exhaust at the rear, the Suzuki design keeps its intake at the back, as on a normal transverse bike engine.

The tilt of the cylinders increases space for the turbocharger in front of the engine. Exhaust exits straight from the cylinders into the turbo, which is good for keeping lag to a minimum. the design also allows a conventional airbox (22) to be fitted in front of the fuel tank (19). The intake air goes into the turbo (23), then to an intercooler (27) to reduce its temperature, and is then piped to an pressurised plenum (33) that feeds the air into the throttle bodies.

This design is obviously far from being a production proposition, but by staking a patent claim to this layout, Suzuki could be hoping to both solve some of the packaging problems that come with fitting a turbo to a bike and to get an advantage over its rivals by preventing them from following the same route.

Share on social media: