Yamaha’s VMAX – the descendent of the original V-Max – dies this year. In August the last of them will roll off the production lines and there’s no sign of a replacement waiting in the wings.

With the current 1700cc V4 bike’s demise we’ll be witnessing the end of a model that can trace its heritage back nearly 33 years to the original 1200cc version’s debut in Las Vegas back in October 1984.

The V-Max, and the VMAX that followed it, are enigmas. They offered big numbers in terms of power, but achieved only small ones when it came to sales. It didn’t inspire a host of rivals or become famous through racing exploits and yet the model achieved a mystique and a hard-core following that means its name is up there with ‘Ninja’, ‘Fireblade’ or ‘Goldwing’ as a motorcycling touchstone. Kids in the 1980s who couldn’t tell a C90 from a VF1000 would recognise the V-Max’s name and its distinctive shape, and know that it was the Top Trump of bikes when it came to sheer power and straight line acceleration.

Origins

The V-Max story starts a few years before that 1984 unveiling, when a group of Yamaha engineers took a fact-finding trip to the USA. Among them was Akira Araki, who’d go on to helm the V-Max project.

Back in 2001 he explained to Yamaha’s own ‘Design Café’ website how the idea came about, saying that they witnessed riders drag racing on a bridge over the Mississippi. “They started from one end of the bridge,” he said, “and the finish line was the opposite side. It was a simple rule. First concept I imagined from this impressive race was to make a bike, which is strong at straight lines and really fast. It was the birth of the V-max concept.”

Early work for the bike was done at GK Design International’s American office, taking inspiration from drag racing hot rods, and early on a V4 engine was chosen thanks to its echoes of the V8 motors used in American cars. Fortunately Yamaha was already working on a new V4, an 1198cc unit developed to power the Goldwing-rivalling 1983 Venture Royale. While that bike is largely forgotten these days, its existence cemented the drivetrain layout that would become the V-Max’s calling card.

V-Boost

There was a sticking point with the new motor, though. It only made around 90hp and was developed with a lazy touring bike in mind.

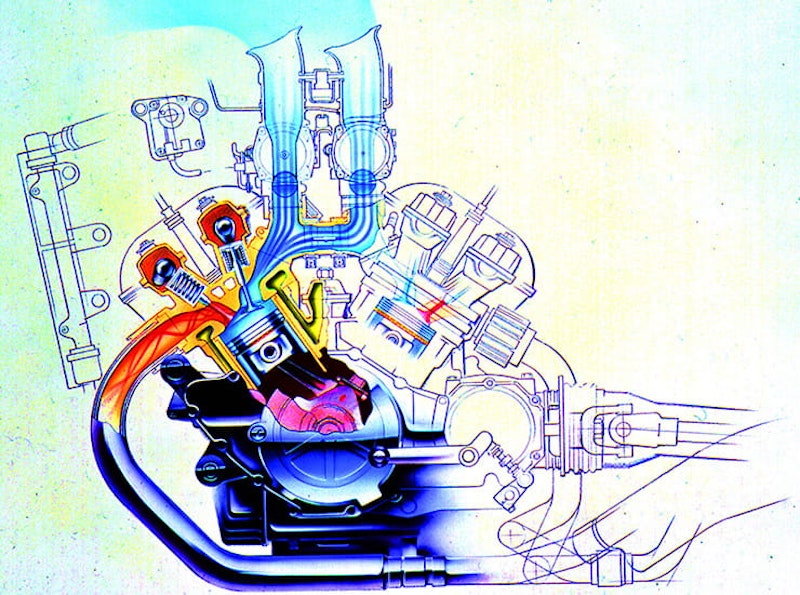

After considering adding a turbo – something that was in vogue in the early ’80s, when each of the Japanese big four developed turbocharged bikes – the firm hit upon the V-Boost idea.

The original V-Max 1200’s V-Boost followed the same thinking that would also lead to Honda’s Hyper VTEC system. Both are designed to address a fundamental compromise between low-end torque and top-end power.

For tractor-like pulling power, as needed for the Venture Royale, engine designers will use small intake sizes. That increases the velocity of the mixture entering the engine, mixing fuel and air better at low engine speeds. But the same small intakes will strangle engines at high revs, limiting peak power.

While Hyper VTEC, as used on the VFR800 to this day, switches from using a single intake valve at low revs to two valves at high revs – doubling the size of the intake – V-Boost does the same trick a different way.

It achieved the doubling of intake size by using a clever intake manifold. The V-Max had four small carbs, one for each cylinder, but the V-Boost system opened butterfly valves in the intake manifold to connect the carbs into pairs above 6000rpm. That meant each cylinder was sucking through two carbs rather than one at high revs, easing its breathing and massively improving power.

The result was remarkable, upping the lazy Venture Royale-based motor from 95hp to a whopping 145hp. In 1984 that was an unimaginable figure; even the GP bikes of the era would struggle to achieve so much power. No other production machine even came close to it.

Not every V-Max was born equal, though. While American models got the full performance, in many markets, including the UK from 1991-1995, the V-Boost system was disabled, limiting power to a Venture Royale-like 95hp and effectively eliminating the entire point of V-Max ownership.

Perhaps unsurprisingly, the restricted bikes didn’t sell in big numbers and even fewer survive today. But if you’re in the market for a V-Max, do double check that the one you buy isn’t a castrated model.

Model history

For a bike that made such a splash when it was launched in 1984, the V-Max’s development was neglected. While American sales were initially strong, they settled down after a couple of years and Yamaha opted to let the V-Max bumble along as it was rather than reinvent it to regain interest.

Yes, there were updates, but usually only to colours and finishes. The rear wheel was changed in 1986, and the V-Boost was improved. The same year European sales started with the low-power version in France. The front wheel was updated in 1987 (’88 in America). In 1990 it gained a new ignition system.

In 1993 there were new forks and brakes, with larger discs and four-pot calipers replacing the old two-pots, and in 1996 the engine was tweaked to add a spin-on oil filter and UK-model V-Maxes finally got American-spec V-Boost systems.

Despite the apparent lack of interest from its maker, the V-Max remained in production in this first-generation form until the end of 2007.

2009 saw the VMAX get a major revamp

Second coming

By the time the 1200cc V-Max died, it was already no secret that a completely new replacement model was on its way.

In one of the first examples of the drawn-out, teasing model launches that have become annoyingly familiar today, Yamaha actually gave us the first clear look at what would become the 2009 VMAX (all in capitals and losing its hyphen) back in 2005, a full two years before it would stop building the original version.

Development of the new VMAX had actually started even earlier, in 2003. Yamaha had recognised that the original was nearing its use-by date and had a choice; update it or start again from scratch. Given the old V-Max’s age, it opted for the latter route.

Speaking at the bike’s launch, Yamaha Europe Product Planning Manager Oliver Grill said: “We didn’t want to fiddle around with small changes. The idea grew stronger and stronger to develop a completely new machine including a new engine.”

And what an engine it was. Yamaha developed the new 1679cc unit from a clean sheet, and with it very nearly managed to become the first production bike to break the 200bhp barrier. Eventually, the firm settled at 200PS – 197.4bhp – instead.

While the new engine, fuel injected rather than carb-fed, didn’t retain the original V-Boost system, Yamaha was keen to preserve the feeling. So it added its YCCI (Yamaha Chip Controlled Intake) instead. This is the system that varies the length of the intake trumpets. At low revs, longer trumpets are used, but at higher engine speeds the top parts lift up, creating a gap between the two halves where additional air can flow in. It was also among the first bikes to get a fly-by-wire throttle, following on from the R1 and R6, and Yamaha’s traditional EXUP valve in the exhaust again helped give an extra kick of top-end power.

The engine actually retained the original 1200cc V-Max’s 66mm stroke length, adding all the extra capacity through the use of a 90mm bore – up from 76mm. That helped it rev to 9500rpm, with the peak power coming at 9000rpm. Not that the engines shared any actual components – the new 1679cc motor’s 65-degree V-angle meant it was actually externally smaller than the old 1198cc, 70-degree V4!

Engine aside, it was all change in the transformation from V-Max to VMAX. Where handling wasn’t a priority for the original bike – it was notorious for being over-engined for its floppy steel-tube chassis – the new one had modern expectations to live up to. A cast aluminium beam frame was the answer. Similarly, the bike was given up-to-the-minute six-pot, radial-mount front brake calipers and hefty 52mm forks. Even so, Yamaha saw it as prudent to electronically limit the top speed to 220km/h (137mph). It was a wise move, as the VMAX, for all its aluminium and modern technology, remained a fatty at 310kg (wet) – that’s actually a few kilos more than its predecessor.

And that, perhaps, was its fatal flaw. For all the excitement over the bike’s power and acceleration, it failed to impress dynamically. To hammer the point home, in late 2010 – when the VMAX 1700 was still in its first flush of youth – Ducati unleashed the Diavel on the world, showing that drag-inspired cruisers could be made to do corners, too. The Diavel might have lagged on the power stakes with 162bhp, but it was lighter, so both bikes would do a standing quarter in the low 10-second bracket. What’s more, the Italian would run all the way to 169mph, handle twisty roads with aplomb, it carried the allure of the Ducati badge and it cost significantly less to buy than the VMAX, too.

The future

In Europe, Yamaha pulled the VMAX from its range at the end of 2016. The bike doesn’t meet EU4 emissions rules that came into force at the start of 2017 and while the firm could have applied for a two-year exemption, it’s opted instead to make sure all its bikes meet the new regulations.

Making the VMAX comply probably wouldn’t have been that tough, after all, its engine is modern and relatively under-stressed, but given its low sales volume the firm clearly decided it wasn’t worth the expense of doing it.

The fact is that the near-200bhp power figure that seemed jaw-dropping in 2009, even for a 1700cc V4, is now around the minimum that manufacturers aim for from their 1000cc fours, whether fully-faired superbikes or naked roadsters. The VMAX’s unique selling point has long since disappeared, so while it still offers a unique riding experience, it’s a harder sell than ever before.

Does that mean it’s the end of the road for the VMAX altogether? Yamaha won’t be drawn, but there’s no sign that a replacement model is high on its priority list. The firm points out that it’s still using the VMAX name, albeit on outboard boat engines, but given that the last new VMAX motorcycle was being teased for years even before its predecessor had been killed, the chances of the firm surprising us all with a new model in the near future are slim to negligible. There are no rumours, no patent filings, no spy shots to suggest that Yamaha has anything VMAX-ish in the pipeline.

The simple fact is that the VMAX has been killed in part by bikes that were never intended to be its rivals. It was dreamt up at a time when bike designers had to make big choices. In the early ’80s you could go fast in a straight line or buy something smaller and lighter that handled well. The sets in that particular Venn diagram didn’t intersect back then.

Now we’re all used to the idea that we can have our cake and eat it. We just have to get used to the fact it won’t be VMAX-shaped.

The Missing Link: Craft GK V-Max

While there’s a common design theme running through the original V-Max 1200 and the 2009-on VMAX 1700, few have seen the bike that connects the two.

It’s this, the Craft GK Design Project 01, which was offered as a custom kit by official Yamaha accessories division Y’s Gear in Japan in 2005.

Produced to order only, it’s thought that no more than 30 of the kits were made. That’s not surprising, as the body kit alone cost 2,100,000 yen (£14,500) with the suspension parts adding an additional 1,680,000 yen (£11,600) to the price. Plus fitting, of course.

However, it did represent an update on the V-Max’s design from its original studio, GK Design, which would also go on to style the new version.

In terms of appearance, it sits directly between the two models. Had Yamaha revamped the V-Max 1200 when it was a decade or so old, rather than letting it go unchanged for 23 years, this is what that revised bike might have looked like. A faired-in headlight, new metal air intakes, new side covers, silencers and seat show how the original style could have been pepped-up by its original designers.